Flowing through eastern Uttar Pradesh, the Tamsa River has long been an integral part of rural life—supporting agriculture, culture, and daily livelihoods. However, like many small rivers across India, it gradually fell victim to neglect. Increasing silt deposits made sections shallow, while plastic waste, household garbage, and encroachments choked its natural flow. What was once a lifeline began to resemble a polluted drain, raising concerns among local communities.

Climate change has emerged as one of the most pressing challenges of the 21st century, impacting ecosystems, economies, and communities across the globe. Rising temperatures, extreme weather events, and ecological imbalances are no longer distant threats—they are current realities. In this context, India is increasingly turning to technological innovation, particularly Artificial Intelligence (AI), to address climate challenges and build resilience for the future. India’s approach to climate action reflects a balance between development and sustainability. Over the years, the country has made notable progress by expanding renewable energy capacity, increasing green cover, and implementing policies aimed at reducing emissions. However, as climate risks intensify, traditional methods alone are no longer sufficient.

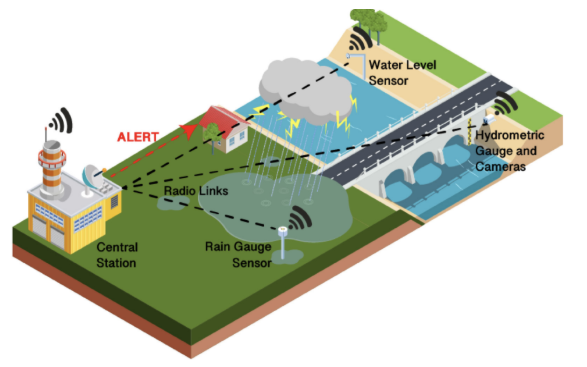

Climate change is increasing the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events across the world. Floods, heatwaves, cyclones, and storms are no longer rare. As these hazards become more common, early action has become one of the most effective ways to reduce damage and loss of life. Early warning systems play a critical role in this context. They do not prevent disasters, but they provide enough time needed to prepare and respond. When warnings are issued in advance, they can significantly reduce deaths and destruction, especially in regions that are highly exposed to climate risk.

Climate change is no longer a future threat to agriculture, it is already shaping how food is grown across the world. Rising temperatures, irregular rainfall, prolonged droughts, and sudden floods and more frequent extreme weather events have made farming increasingly uncertain. In many regions, the question is no longer whether climate change will affect agriculture, but how severely and how soon. In this context, climate-smart agriculture is often presented as one among several possible responses. For large sections of the farming population, however, it has become a matter of survival rather than choice.

In the lush, mist-shrouded hills of India’s Northeastern state of Tripura, a different rhythm of life unfolds — one that balances human needs with nature’s limits. As Tripura celebrates its Foundation Day, it offers more than historical reflection; it invites the nation to rethink development through a sustainable lens shaped by local wisdom and ecological harmony.

A stark new analysis from the University of Oxford has sounded a serious alarm bell about the near-future trajectory of global temperatures and their human impacts. The study finds that if current warming continues and the planet reaches roughly 2 °C above pre-industrial levels by 2050, almost half of the world’s population — about 3.79 billion people — will be living under conditions defined as extreme heat. This significant increase in global heat exposure underscores a rapidly intensifying climate crisis that threatens health, livelihoods, and social structures across continents.

Limiting global warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels is not just a global climate goal. It is a critical survival threshold for India. Because of India’s large population, climate-dependent economy, and ecological diversity, even a small increase in average global temperature can translate into severe and unequal impacts on people, livelihoods, and natural systems.

In a time when water scarcity, pollution, and environmental degradation are pressing challenges across India, one young changemaker is turning the tide — one pond at a time. Ramveer Tanwar, known widely as India’s Pond Man, has dedicated himself to restoring once-thriving ponds and lakes that had been reduced to dumping grounds filled with garbage, debris, and disease-carrying waste. His remarkable journey — from a corporate career to full-time environmental restoration — is a testament to the power of individual commitment and community mobilisation.

A chilling new analysis warns that by 2050, climate change could cause up to 15 million additional deaths worldwide. The figure may appear abstract, but behind it lies a grim reality—millions of people could lose their lives due to extreme heat, floods, droughts, food insecurity, disease outbreaks, and failing health systems. As the planet warms, the human cost of inaction is becoming painfully clear.

India’s Western Ghats — one of the planet’s most biologically rich landscapes — is now under serious threat. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has flagged the region as in a state of “significant concern”, pointing to climate change, infrastructure development, tourism and plantations as major stressors.